Christmas, Then and Now

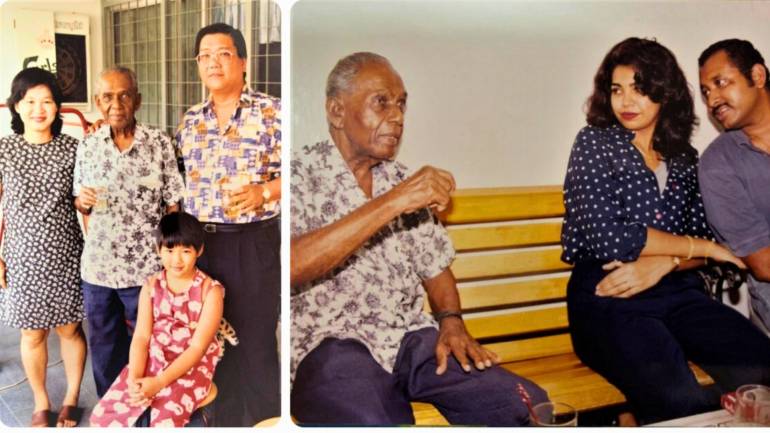

Over the years, some siblings who shared my childhood Christmases have quietly slipped away. One by one, voices that once filled the house have fallen silent. With them went a certain warmth, a kind of innocent, unselfconscious bonding that only siblings know, and only time can take.

Brothers Gabriel, Michael, Anthony, Peter, and Francis, each carrying a different temperament, a different way of being “Christmas-ly” present are no more.

Peter, who passed on December 5, was the family’s great goalkeeper, agile and unafraid to throw himself into the moment. Perhaps now he keeps watch at another gate altogether, faithful still, guarding not a goalpost but the celestial entrance of Paradise.

There was also a sister, Anne, whose quiet attentiveness held things together more than we realised at the time. My father, Joseph Sr, whose steady presence anchored Christmas even when words were few. And Delphine Anderson, a sister-in-law - but more a magician by instinct, who somehow made toys appear, wrapped and ready, turning scarcity into surprise.

Each of them lent Christmas something unique, something that could not be replaced once they were gone.

Gabriel brought calm. Michael brought evergreen ferns for the tree. Anthony brought watchfulness. Francis brought warmth. Peter brought vigilance the kind that stays awake for others. Anne brought care without announcement. Joseph Sr brought order, dignity, and the assurance that Christmas would come, no matter what the year had taken away. And Delphine brought wonder the quiet kind that children never question, but adults never forget.

Among them were my twin brothers, Noel and Emmanuel, names heavy with Yuletide meaning even then, though we barely noticed. “Noel”, the season itself. “Emmanuel”, God-with-us. As children, they were simply brothers, inseparable, mischievous, alive. Only later does one realise how profoundly Christmas had already named them, and through them, named us.

They are gone now.

What remains are memories, fragile yet persistent, like the vestigial scent of something once familiar.

As a child, Christmas in Malaysia in the sixties arrived without fuss. There was no excess, no hurry. The season announced itself through preparation rather than spectacle, a house made ready, clothes laid out carefully, the slow building of anticipation.

Christmas had texture then: the creak of wooden floors, the rustle of wrapping paper saved and reused, the quiet thrill of staying awake far past bedtime, just to watch the older siblings put up the decorations.

Flavour Of Grilled Meat

The whiff of roasted turkey emerging from the oven, prepared with care by a Hainanese chef, Yap Kim Moh, who understood that Christmas was not merely a meal, but a ritual. The aroma filled the house and lingered long after, settling into memory. To this day, it remains inseparable from Christmas itself, warmth, patience, and craft folded into one.

Toys were modest. Often shared. Sometimes argued over. But they were never the point. The real gift was togetherness, siblings gathered, laughing, teasing, quarrelling, reconciling. In those moments, Christmas was not something we observed; it was something we inhabited.

As children, we did not know we were living inside something that would one day ache.

Christmas then was about receiving. Faith was present, but gently so. The Baby Jesus lay in the manger, but He belonged to the grown-ups, to hymns, incense, and the seriousness of Midnight Mass at St Phillip’s Church.

For us, Christmas was joy first, meaning later. There was no shame in that. Childhood is allowed its innocence. Joy arrives before understanding.

Time, however, rearranges Christmas.

As a Catholic adult, Christmas now arrives with memory attached, and memory brings both gratitude and grief. The house is quieter. Chairs are empty. Names are spoken inwardly, sometimes only in prayer. The season no longer distracts from loss; it exposes it.

And yet, faith deepens precisely here.

The Christ Child is no longer only tender. He is vulnerable. He enters not into fullness, but into absence. Not into crowded rooms, but into spaces hollowed out by those we loved. The manger speaks more clearly now because they understand emptiness.

As a child, Christmas said: You will receive. As an adult, Christmas asks: Can you still believe when so much has been taken away? The answer, slowly learned, is yes, but differently.

Emmanuel

Christmas no longer promises that nothing will be lost. It promises that nothing loved is wasted. “Emmanuel” God-with-us, is no longer a title learned in catechism. He is presence itself: in grief remembered without bitterness, in bonds that death has not erased, in love that continues to shape us even in absence.

The toys of yesterday brought delight. The Christ of today teaches endurance.

As a child, one relied on elders to make Christmas happen.

As an adult, one realises Christmas survives through fidelity, the choice to gather when it hurts, to forgive when it is tiring, to remember without despair.

Christmas becomes less about celebration and more about watchfulness.

And yet, something of the child must remain. Faith that forgets wonder becomes brittle. Faith that forgets joy becomes heavy. Perhaps adult Catholic faith is not about abandoning the Christmas of childhood, but carrying it, baptised by loss, matured by love.

The roasted turkey is now only a memory. The siblings are names spoken softly.

The laughter has thinned into silence.

But the manger remains.

And in that manger lies a God who understands loss, who enters history knowing He will be mourned, betrayed, and missed, and still chooses to come. Not to remove suffering at once, but to dwell within it, to redeem it from the inside.

Between the toys once shared and the loved ones now gone, the heart learns that Christmas is not about holding on - but trusting that love, once given and shared, is never lost forever.