“Church Has No Official Stance either For or Against Extraplanetary Life”

An interview with Father Richard Anthony D’Souza, the new director of Vatican Observatory

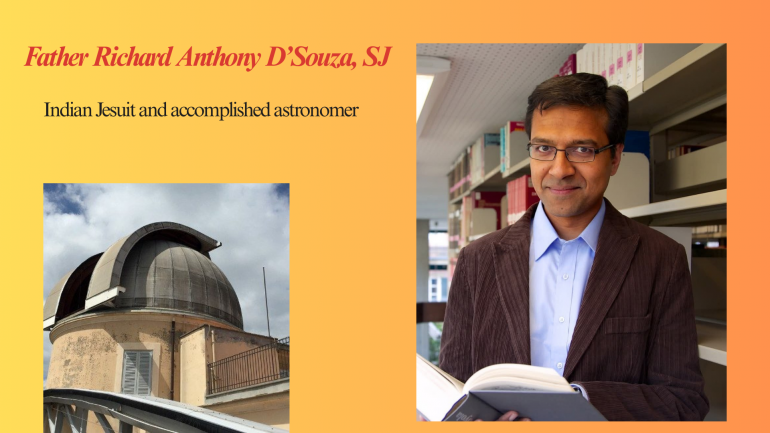

Pope Leo has appointed Father Richard Anthony D’Souza, SJ, an Indian Jesuit and accomplished astronomer, as the new director of the Vatican Observatory, one of the world’s oldest centers for astronomical research.

Father D’Souza, who officially takes office on September 19, succeeds Brother Guy J. Consolmagno, SJ, and brings with him a rich academic and research background in the formation and evolution of galaxies.

In a conversation with Radio Veritas Asia correspondent Tom Thomas, Father D’Souza spoke about his lifelong interest in astronomy, the Jesuits’ contributions to the field, the mission of the Vatican Observatory, merging galaxies, life on other planets, and his message for aspiring astronomers.

Excerpts:

A Jesuit and an astronomer – how did that happen?

Right from an early age, I have been interested in the sciences. In the beginning, I was more interested in physics and engineering, but over the time, I got drawn to astronomy. In the Jesuit high school I attended, I got to know the Society of Jesus. It is there that my vocation was born, and I joined the Jesuit novitiate soon after I finished high school.

Could you share how your education and priestly formation shaped your path as both a Jesuit and an astronomer?

I was born in 1978, and my early schooling took place in Kuwait. In 1990, my family returned to my home state of Goa, India. After completing my studies at the Jesuit-run St. Britto High School, I entered the Society of Jesus in 1996. I graduated in Physics from St. Xavier's College, Mumbai, in 2002, and then pursued a Master’s degree in Physics at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, where I completed my thesis at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy.

I returned to Pune in 2005 to continue my priestly formation. After obtaining bachelor’s degrees in philosophy and theology, I began my doctoral studies in Astronomy at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching, Munich, earning my Ph.D. in 2016. That same year, I formally joined the staff of the Vatican Observatory while also starting a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. In 2019, I moved to the Vatican Observatory headquarters in Castel Gandolfo. Since 2022, I have been serving as the Superior of the Jesuit community attached to the Vatican Observatory.

Can you please trace how the Jesuits came to be associated with astronomy in the history of the Catholic Church and how the tradition continues to this day?

The Society of Jesus has had a long tradition of Jesuits working in the sciences, astronomy included. Right from the early days, many Jesuits were associated with various Papal observatories over the centuries. Many of them made important contributions in astronomy. I would like to highlight a few of them. Fr. Christopher Clavius was involved in the reform of the calendar. Fr. Giovanni Battista Riccioli was the first to draw a map of the moon and begin to give names to the various craters. Fr. Angelo Secchi was the first to systematically study the spectra of stars and begin to classify them. The Jesuit spirituality, which is incarnational, encourages us to “find God in all things.” Our founder, St. Ignatius of Loyola, himself received great consolation from gazing at the sky and the stars, and encouraged us to see how God was working and labouring for us in His creation. The results of our scientific research can become a way to praise God as we marvel at His creation.

Can you explain to us a little bit about the mission of the Vatican Observatory today?

The present Vatican Observatory was refounded in 1891 by Pope Leo XIII within the walls of the Vatican. Its mission, as defined, in the Motu Proprio of Pope Leo XIII Ut Mysticum, is to be of service to the Pope and the Universal Church, to show the world that faith and science can go together, and that the Church is not opposed to true and good science.

Today, the Vatican Observatory conducts a wide range of astronomical research, from studying meteorites, near-Earth objects, planets, extra-solar planetary systems, stars and stellar structure, galaxies, cosmology, to quantum gravity and the Big Bang. After the publication of Laudato Si’, the Observatory has ventured into the field of meteorological and climate research. Each of the various members of the Vatican Observatory is inserted in a unique field of research, collaborating with colleagues in that field of study. In this way, the Observatory reaches out to a large number of scientists. The Observatory regularly organizes important conferences in Rome or Castel Gandolfo, as well as collaborates with the Pontifical Academy of the Sciences.

Can you share something about your area of specialization, the merging of galaxies?

One of my primary research questions is to understand how the present-day properties of galaxies are influenced by the merging of galaxies. During its lifetime, a galaxy like our own Milky Way merges with thousands of smaller galaxies. To understand how these mergers affected the present-day properties of our galaxy, one must infer the past mergers of a galaxy, just as an archeologist would do to retrace the past history of an object. One does this by studying the faint light present in the outskirts of the galaxy, which is very difficult to observe. But this outer light contains information about the galaxy’s past. Through my research, I was able to demonstrate how it was possible to constrain the mass and the time of the merger of the largest satellite galaxy, which merged with the main galaxy.

We applied this methodology to our nearest neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy, and inferred that it must have merged with a large galaxy about 2 billion years ago, which was half the size of the Milky Way. We postulated that such a large galaxy once existed and was devoured by the Andromeda galaxy. We also postulated that the remnant of this galaxy still exists today in the form of the enigmatic galaxy M32, which has defied explanations till now. Hence, the large galaxy that was destroyed was named “M32p,” or the progenitor of M32. One of the hints that led us to identify M32 as a possible remnant galaxy was its high density, much higher than the cores of most galaxies, much like a peach whose flesh has been peeled away, leaving behind the hard core of the seed.

You are one of the lucky few to have an asteroid named after you! How did it happen?

In June of this year, an asteroid 671271 (or 2014 HJ308) was named after me. It was discovered by K. Cernis and R. P. Boyle SJ with the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope on Mount Graham in 2012. It is presently found in the outer part of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. This honor adds to the list of more than 30 asteroids named after Jesuits.

An asteroid is awarded a name once it has been observed long enough for its orbit to be determined with a fair degree of precision. This may take several years, but when it is achieved, the body is awarded a “permanent designation” (a number issued in numerical sequence) and the discoverer is invited to suggest a name for approval to a special committee of the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Could the astronomy-related scenarios mentioned in the Bible, such as the star that the Magi saw, be explained?

Today scripture scholars interpret such events more as tools to convey a doctrinal truth. While the Star of the Magi may have been connected to some real astronomical event, the more important aspect of the narrative is the theological truth, that Christ’s birth was announced to the world. Although several hypotheses have been proposed over the years, we still do not know the exact physical phenomenon that corresponds to the Star of Bethlehem.

What is the Church’s stance on the possibility of life on other planets and the creation of the Universe by the Big Bang?

The Church upholds the theological truth that God created the world from nothing and that He created all things good. Beyond this, it does not define precisely how God created the Universe. It is worth noting that the Big Bang theory was proposed by a Belgian priest, Fr. Georges Lemaître, who applied Einstein’s theory of relativity to cosmology. Initially, his theory faced opposition from some scientists who did not wish to engage with the theological and philosophical implications of a Universe with a beginning. Over time, as more evidence emerged, it became the prevailing cosmological model.

One of the major areas of research in astronomy today is the search for life on other planets. More than 2,000 exoplanets have already been discovered through various methods. Using advanced instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers are now analyzing starlight filtered through these planets’ atmospheres to detect molecules that might indirectly suggest the presence of basic life forms.

The Church does not have any opinions for or against the possibility of life on other planets. Such a discovery, when confirmed, could spur a lot of new theological discussion.

What is your message for young students aspiring to pursue astronomy?

First of all, be curious, passionate, and ready to challenge the limits of our knowledge. Second, don’t settle for superficial answers; seek deeper truths, because reality is often far more complex than it appears. Third, be prepared for hard work and occasional disappointments; a career in science is demanding and not for the faint-hearted.

If you truly wish to embark on the journey of becoming a scientist or astronomer, try to gain some research experience early on, whether through a small project with a scientist during your studies or an internship later. This will give you a real taste of what research involves.

Finally, choose a good research advisor, someone who can guide you well and with whom you have a good working relationship. Science is not only about rational thinking; it’s also a collaborative endeavor built on friendships and teamwork.